TL;DR

Via's memory system was surfacing learnings at a 3.2% rate — 69% of stored knowledge had no embeddings, so hybrid search was falling back to keyword-only matching. Completing the embedding backfill and adding three Claude Code hooks (pre-compaction flush, post-compact inject, session-end snapshot) brought retrieval to 34.7%. The database compacted from 2,098 to 992 learnings while becoming more useful.

The 3.2% Problem

I ran orchestrator learnings stats on a Tuesday and stared at the number. 3.2% retrieval rate. We had 1,469 learnings in SQLite with hybrid search, semantic deduplication, and typed bucket retrieval. The system was architecturally sound. And it was surfacing relevant knowledge 3.2% of the time.

The concepts post explained the framework — Google's CoALA memory types, OpenClaw's four lifecycle mechanisms, the audit that showed Via implementing 1 of 4. This post is about what I actually built to close the gaps, and the surprise that the biggest improvement had nothing to do with new features.

The Boring Fix That Changed Everything

The hybrid search formula is 0.3 × FTS5 + 0.7 × cosine similarity. Seventy percent of the score depends on embedding vectors. When I checked coverage, 460 out of 1,469 learnings had embeddings. That's 31.3%.

Seventy percent of the scoring formula was operating on 31.3% of the data. The system was effectively running keyword-only search for two thirds of the database.

The backfill command already existed. I'd built it weeks earlier and never run it to completion. The fix was literally:

Cost: roughly $0.002 in Gemini API calls. Time: under a minute. Impact: every learning in the database now participates in semantic search.

This is the kind of thing that's embarrassing to write about, but it's the most honest part of the story. I spent weeks designing a sophisticated retrieval pipeline, wrote 856 lines of db.go with FTS5 triggers and cosine similarity scoring, and the bottleneck was an unfinished batch job. ADR-1 in the architecture doc said "fix data before adding complexity." I should have listened sooner.

Three Hooks for Three Lifecycle Moments

With retrieval actually working, I turned to the gaps the OpenClaw audit identified. Via was missing pre-compaction flush and session snapshots — the two mechanisms that prevent knowledge loss at context boundaries.

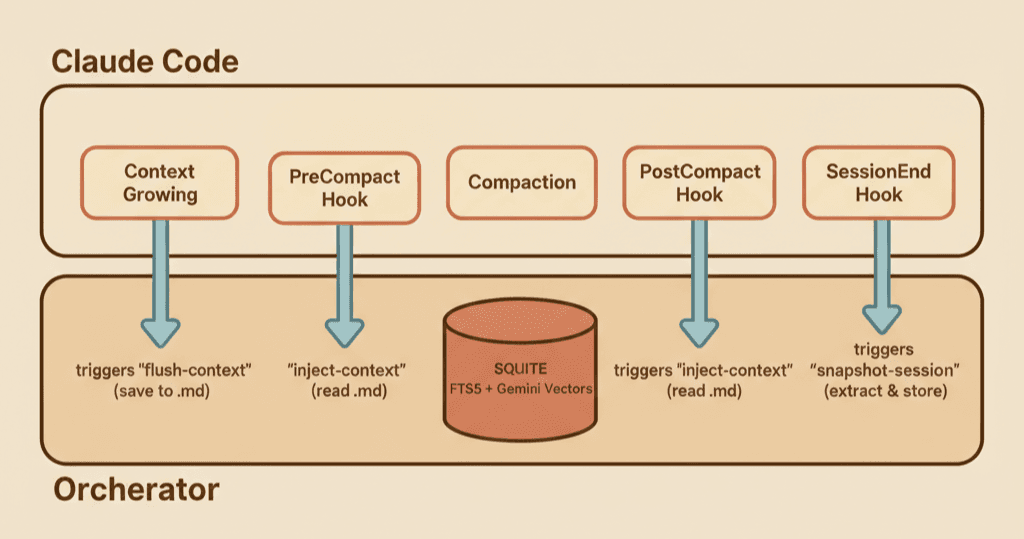

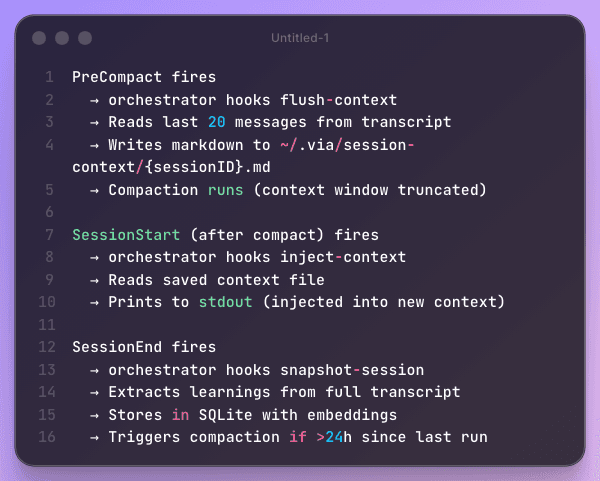

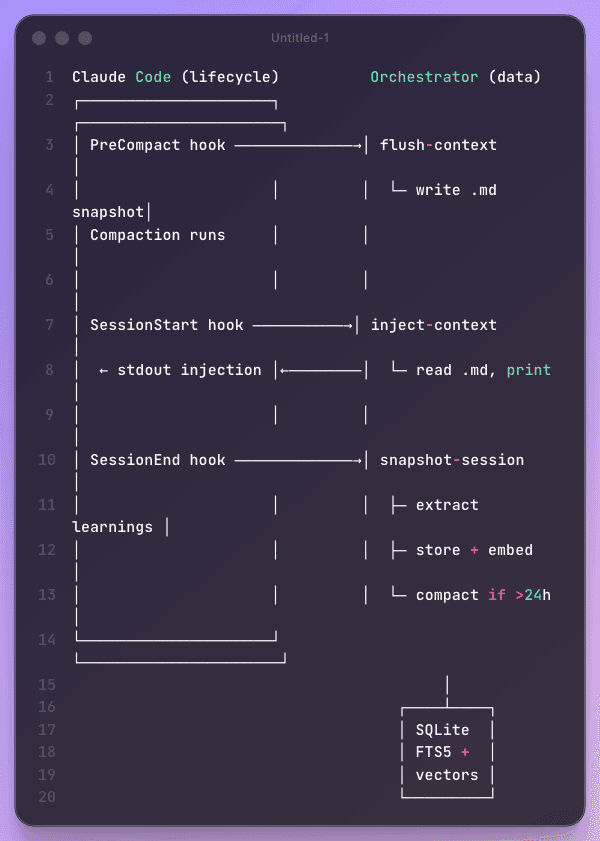

Claude Code's hook system fires at specific lifecycle moments. I built three subcommands that the orchestrator registers as hooks:

The key architectural decision: Claude Code owns the lifecycle, the orchestrator owns the data. The hooks are thin — they call into the orchestrator's learning package, which handles all the storage and retrieval logic. This means Claude Code doesn't need to know about SQLite or embeddings, and the orchestrator doesn't need to know about context windows or compaction timing.

The Flush That Saves the Desk

The pre-compaction flush was the mechanism I most wanted from OpenClaw's design. When a context window fills up and Claude Code runs compaction, everything that wasn't explicitly saved gets truncated. It's the desk-clearing metaphor from the concepts post — except without a flush, you're clearing the desk into the trash.

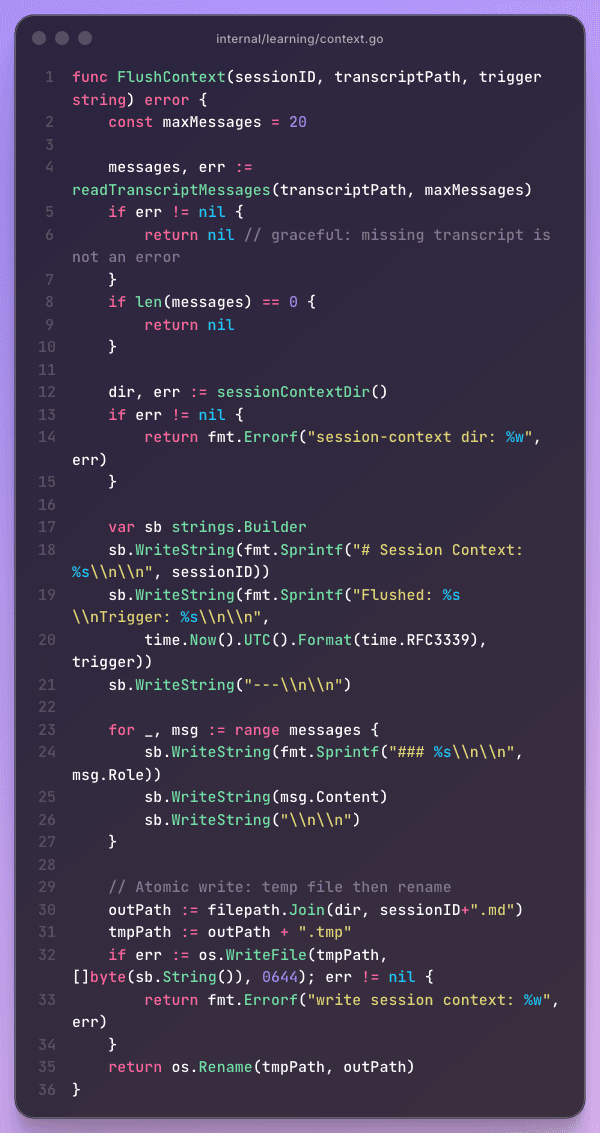

Two design choices worth noting. First, graceful degradation: a missing transcript is not an error. Hooks run in constrained environments with timeouts, and a failure in the flush should never block compaction. Second, atomic writes via temp-file-then-rename — the same pattern databases use for write-ahead logs. If the process dies mid-write, you get either the complete previous file or nothing, never a corrupted half-write.

The Snapshot That Closes the Loop

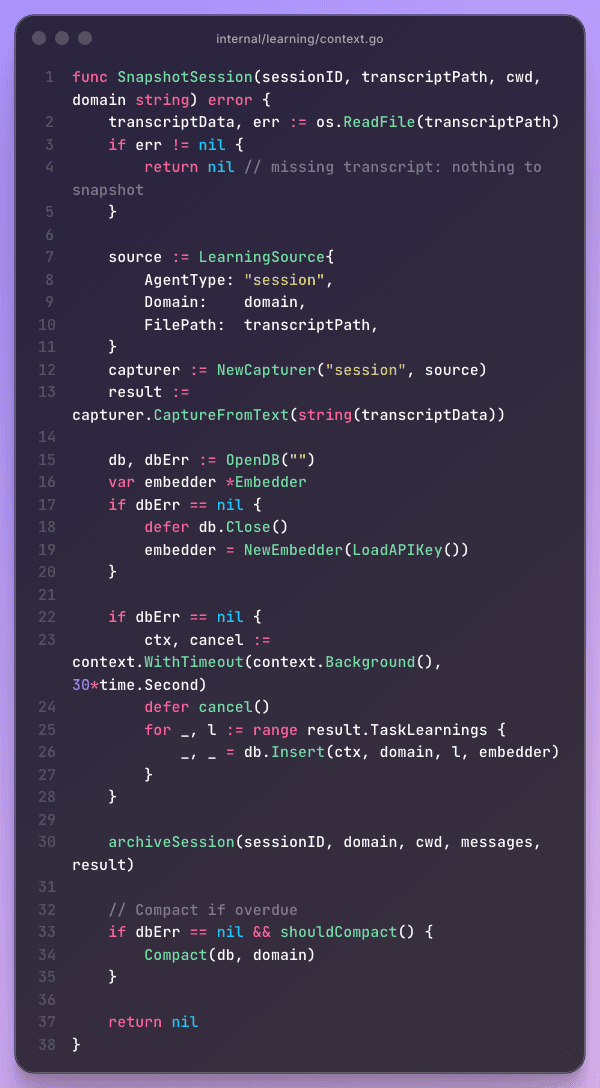

The session-end snapshot is the other side of the coin. Where the flush saves context during a session, the snapshot extracts knowledge after one. It reads the full transcript, runs the same learning capture pipeline that processes agent output, and stores any new learnings with embeddings.

The snapshot also triggers compaction when it's been more than 24 hours since the last run. This is how the database went from 2,098 learnings to 992 — the dedup pipeline (cosine similarity > 0.85 = duplicate) finally had full embedding coverage to work with, and it merged hundreds of near-duplicates that had been invisible to keyword-only comparison.

The Results

Here's the before/after from orchestrator learnings stats:

| Metric | Before | After | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total learnings | 2,098 | 992 | -52.7% (compaction) |

| Embedding coverage | 31.3% (460/1,469) | 100% (992/992) | Full coverage |

| Retrieval rate | 3.2% | 34.7% | 10.8× improvement |

| Learnings actually used | ~16 | 120 | 7.5× |

| Surfaced (seen > 1) | Unknown | 346 | 34.9% of DB |

| Never surfaced | ~1,400+ | 571 | Down significantly |

| Hook subcommands | 0 of 3 | 3 of 3 | Complete |

The 10.8x retrieval improvement came primarily from the embedding backfill, not from the hooks. The hooks prevent future knowledge loss — their value compounds over time as sessions accumulate. But the immediate, measurable gain was fixing the data.

The database shrinking by 52.7% is a feature, not a bug. With full embedding coverage, the dedup pipeline could finally detect semantic duplicates across the entire corpus. "Use FTS5 for full-text search" and "SQLite FTS5 provides full-text indexing" collapsed into a single entry with seen_count: 4. Fewer learnings, higher signal.

The Architecture

The final system has a clear boundary between Claude Code and the orchestrator:

Claude Code fires hooks at lifecycle boundaries. The orchestrator handles everything else — reading transcripts, generating embeddings, deduplicating, storing, retrieving. Neither system needs to understand the other's internals. The hooks are configured in ~/.claude/settings.json with timeouts (10s for flush, 5s for inject, 15s for snapshot) and graceful failure — a hook timeout never blocks Claude Code's operation.

The Honest Limitations

Episodic memory is still thin. The session-context directory is functional but young. The flush-inject cycle works mechanically, but I haven't measured whether the injected context actually changes agent behavior. A hook that fires and writes a file is not the same as a hook that makes agents better.

Procedural memory is untouched. The OpenClaw audit scored Via at 1 of 4 mechanisms. We're now at roughly 3 of 4, but all gains are in the semantic and episodic layers. Procedural memory — dynamically learning how to do things, not just what happened — remains static. CLAUDE.md files and skill definitions don't evolve on their own.

571 learnings have never been surfaced. That's 57.6% of the database. Some of these are genuinely niche — a learning about a specific API that only matters for one type of task. But some are probably relevant and falling through the scoring formula. The hybrid search weights (0.3 keyword + 0.7 semantic) were set by intuition, not by measurement.

74 orphaned MEMORY.md files remain. The consolidation batch to merge these into the central store is designed but not yet run. Each file is a Claude Code project-level memory that the orchestrator can't see — knowledge siloed by accident.

Compaction is lossy. Going from 2,098 to 992 learnings means 1,106 entries were merged or dropped. The dedup threshold (cosine > 0.85) is aggressive enough to catch true duplicates but might occasionally merge learnings that are similar in language but different in context. I chose aggressive dedup over database bloat, but the tradeoff is real.

Related Reading

- How AI Agent Memory Actually Works — The concepts post: CoALA framework, OpenClaw's mechanisms, and Via's 1-of-4 audit

- Teaching AI to Learn From Its Mistakes — Via's semantic memory: capture, dedup, and injection

- How Multi-Agent Orchestration Works — The orchestrator that spawns agents with dynamic context

- What 1,600+ AI Learnings Reveal — Data analysis of the learnings database before compaction