Why I Built This

On a feature team, you touch slices of a product. You build the auth flow, or the dashboard, or the API layer. You never own the whole thing. You never feel the full weight of a product from empty directory to something a person could actually use.

I wanted to know what that felt like.

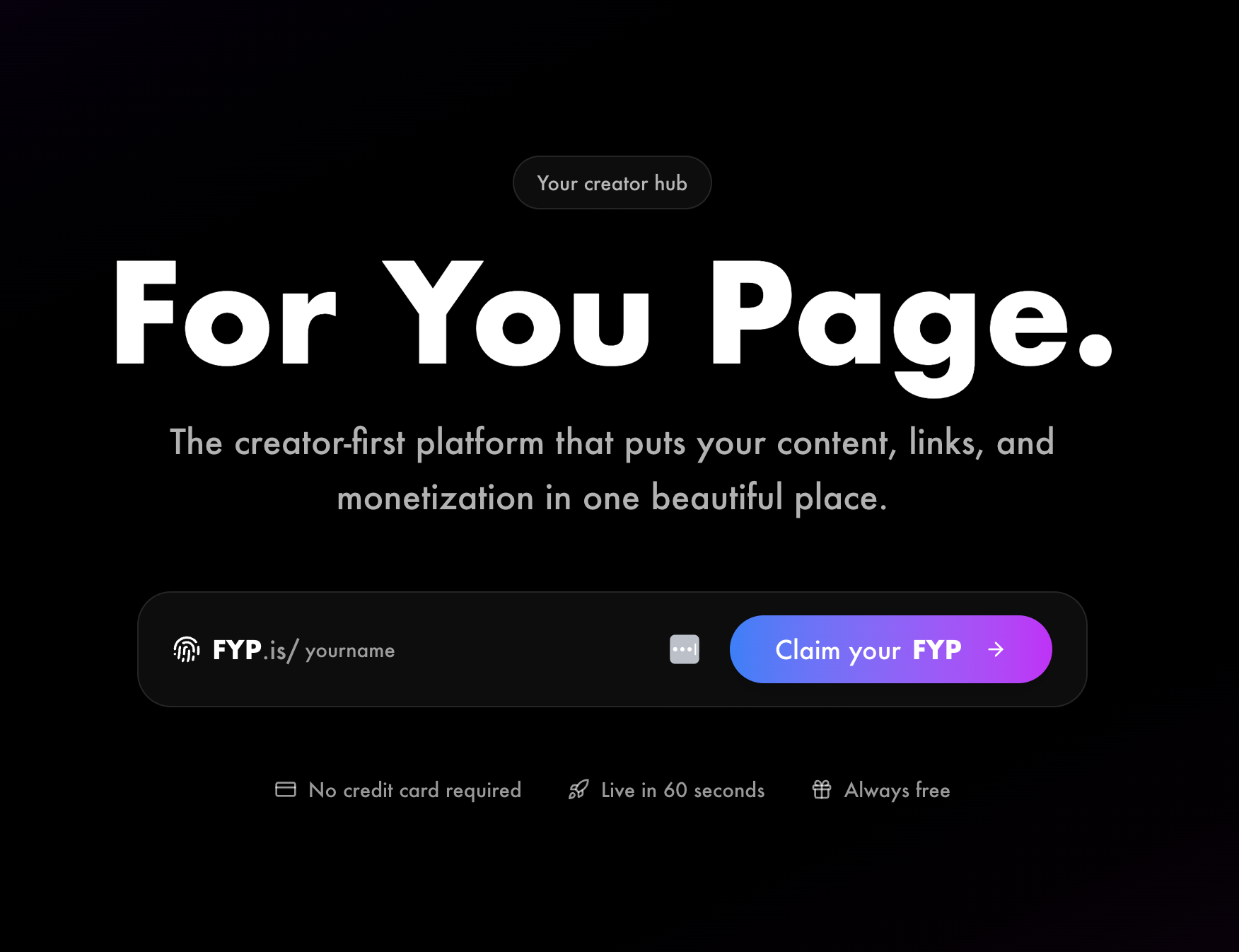

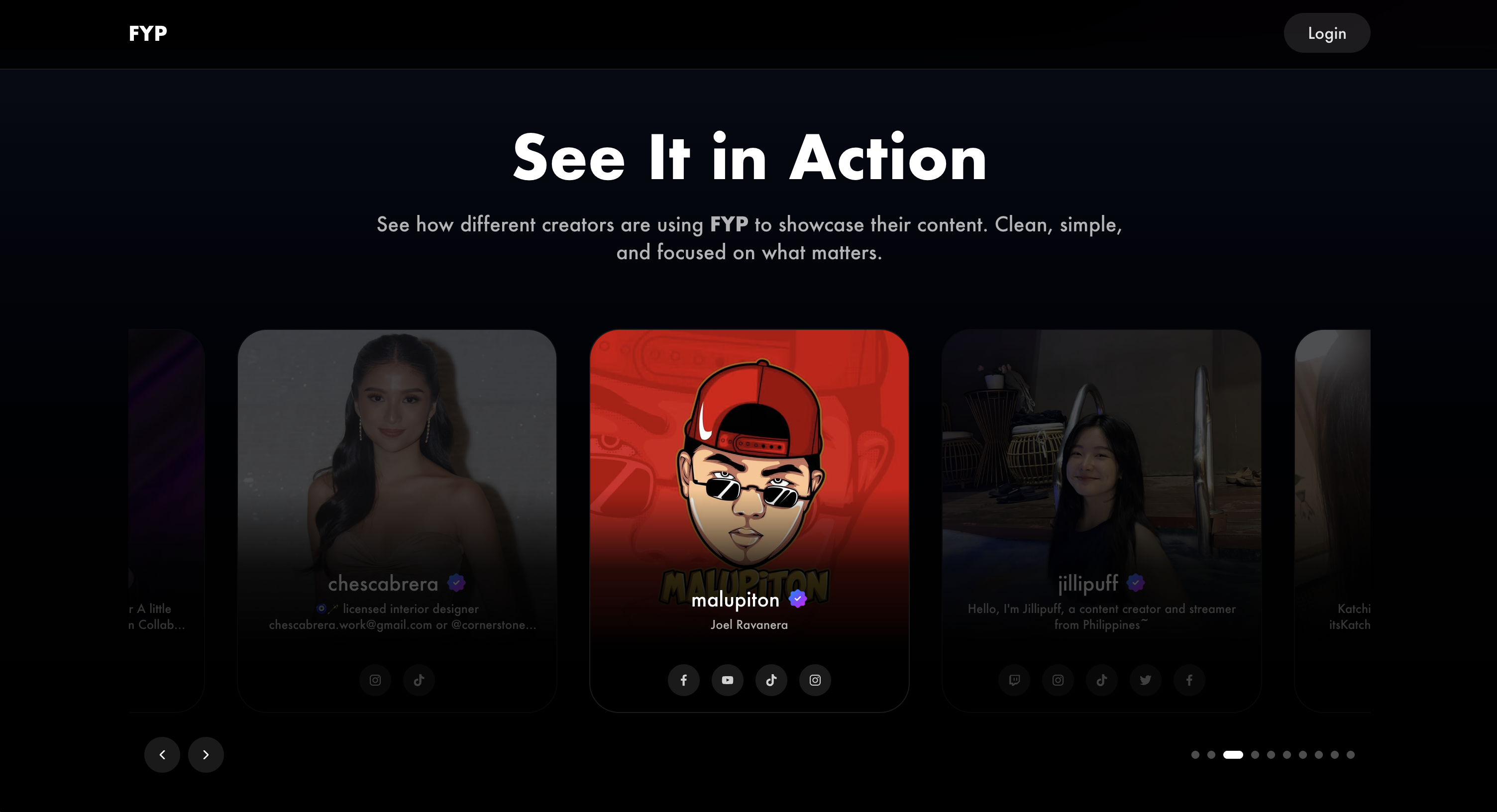

FYP is a creator platform. Think Linktree, but with more ambition. Profile management, 55+ social platform integrations, drag-and-drop link reordering, AI-powered bio generation. The idea itself isn't the point. The point was building something real, end-to-end, with no one to hand things off to.

No designer. No PM. No backend team. Just me, a blank repo, and ten months.

Wearing Every Hat

When there's no designer, you make fifty small design decisions a day. Border radius. Spacing. Whether that button should be primary or ghost. Whether the empty state needs an illustration or just a sentence. Nobody reviews these decisions. You ship them and live with them, and over time you develop opinions you didn't know you had.

When there's no architect to tell you "that's over-engineered," you find out for yourself. I built abstractions I later ripped out. I wrote a custom hook for something that TanStack Query already handled. I spent a full afternoon on a caching strategy for a page that gets hit maybe twice a day. These aren't mistakes you make twice.

When there's no PM to say "not this sprint," you say yes to everything. Celebrity account claiming. Username reservation. AI bio generation. Verification badges. You build it all because it sounds cool, and then you realize why PMs exist. Scope isn't a constraint imposed on you. It's a gift.

The thing nobody tells you about wearing every hat: you get faster at switching contexts, but you never get deep enough in any single one. A designer who designs full-time will always out-design you. An architect who reviews systems all day will catch things you miss. Solo work teaches you breadth, but it also teaches you the value of depth you don't have.

The Decisions That Reveal Values

Every tech stack choice on a solo project is a statement about what you actually believe, not what you think sounds good in an interview.

DrizzleORM over Prisma. I picked Drizzle because I care about type safety more than I care about convenience. Prisma generates types from your schema. Drizzle makes your schema the types. The difference sounds subtle until you refactor a database table and watch TypeScript catch every downstream breakage at compile time. That matters more to me than a nicer migration CLI.

Better Auth instead of rolling my own. I'm good enough to build auth. I've done it before. But auth is the kind of thing where "good enough" isn't. One edge case you miss, one token you don't invalidate properly, and you've got a real problem. Better Auth exists because smart people have already thought about the edge cases I'd forget. Knowing when not to build something yourself is a skill that solo work forces you to develop fast.

Cloudinary for images. Image processing is a trap. You think it's simple. Resize, crop, serve. Then you need responsive variants, format negotiation, CDN delivery, and suddenly you've spent a week on infrastructure that has nothing to do with your product. Cloudinary handles all of it. I moved on to things that actually matter.

@dnd-kit for drag and drop. I tried building drag and drop from scratch once. Once. The browser's drag API is a horror show. Accessibility alone makes it worth using a library. With @dnd-kit plus TanStack Query's optimistic updates, links reorder instantly on screen while the server catches up. It feels native. That's the goal.

Each of these choices taught me the same lesson from a different angle: know where your effort creates value and where it doesn't. Building your own ORM teaches you nothing your product needs. Picking the right one and moving on does.

What Solo Teaches You That Teams Don't

Solo work teaches you ownership in a way that no team structure can simulate. When the build breaks at midnight, you fix it. When a user hits a bug, it's your bug. There's no ambiguity about who's responsible. You feel every dependency you add because you're the one who'll debug it when it breaks. You understand why tests matter because there's no QA team between you and your users.

You also develop a sense for the true cost of features. On a team, a feature request is a ticket. Solo, a feature request is three days of your life. You start asking "is this worth building?" in a way you never do when someone else is prioritizing your backlog.

But solo has blind spots. Real ones.

Nobody tells you your API design is inconsistent. Nobody points out that your component naming convention drifted halfway through the project. Nobody says "this error message is confusing" because nobody's reading your error messages but you. You miss things that a fresh pair of eyes would catch in five minutes.

I caught myself building features I wanted to build instead of features the product needed. On a team, someone would've pushed back. Solo, you're both the person with the idea and the person who approves it. That's a dangerous loop.

The honest answer is that solo and team work teach you different things, and neither one is complete. Solo taught me to think in whole products. Teams taught me to think in systems. I need both.

Is It Ever Done?

There's no deadline on a personal project. No client waiting. No sprint review where you demo what you shipped. The temptation is to polish forever. One more feature. One more refactor. One more edge case handled.

At some point I had to ask myself: is this done enough to have been worth doing?

The platform works. Profiles render. Links reorder. The AI generates bios that are actually useful. Social platforms detect and display correctly. Auth works. Images upload and serve. It does what it set out to do.

But "done" on a personal project isn't about feature completeness. It's about whether you learned what you came to learn. I came to learn what it's like to own a whole product. I learned that. I learned where I'm strong (architecture, data modeling, making things work) and where I'm weak (visual design, knowing when to stop). I learned that building alone is both freeing and limiting, and that the best work probably happens somewhere in between.

FYP isn't a product I'm trying to sell. It's a product I built to find out what I'm made of. Ten months later, I have a pretty good answer.